Yiddish & Kids

Supplementary Links, Resources, and an Interview with Sarah Schulman

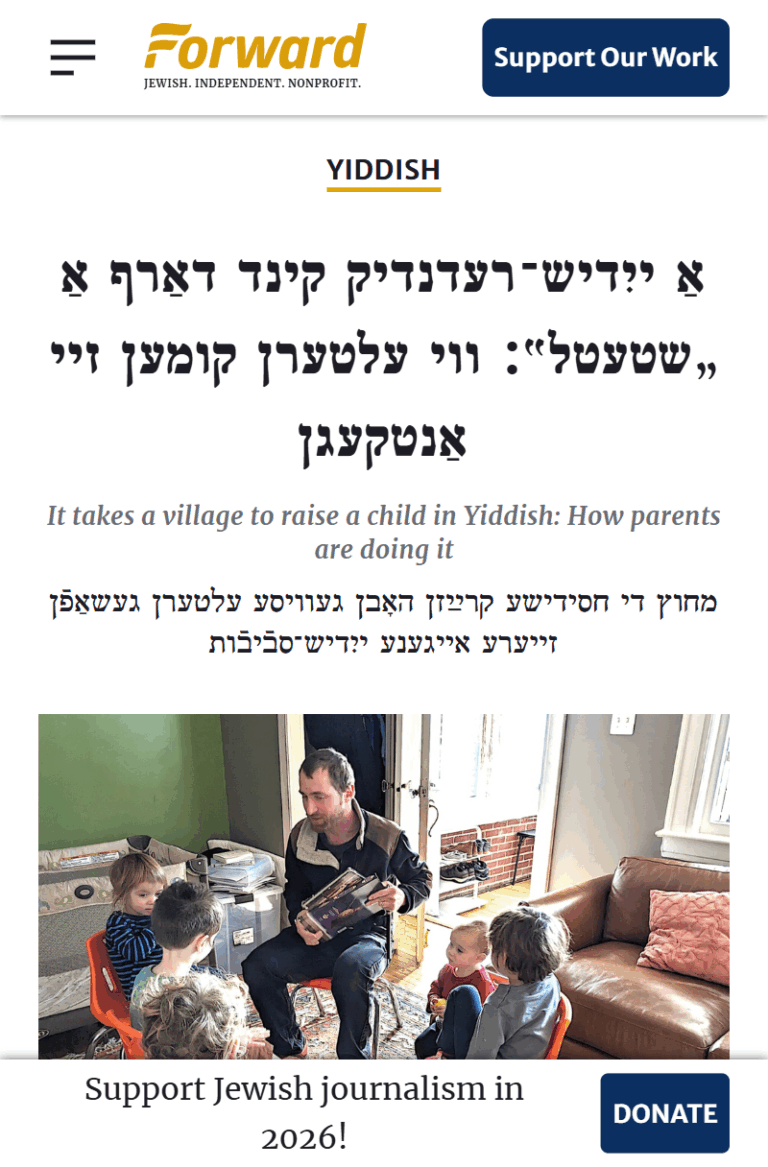

When reporting the article “It takes a village to raise a child in Yiddish: How parents are doing it,” published in Yiddish in the Forverts (18 December 2025), I came across a wealth of stories, resources, and information about a topic that clearly deserves more public discussion in the Yiddish world: how parents can come together to share Yiddish language and culture with their children. These collaborations are beneficial even for families that mostly speak other languages at home. My article centered on the very rare cases of Yiddish-speaking families outside Hassidic Communities, but this supplement extends beyond them.

One pattern that stuck out was that many of these projects involve three or four families with children of similar ages, so that’s the ideal starting place for building a community (or “shtetele”) that goes beyond your own family. This page includes advice and resources useful to both individual families and “shtetelekh” consisting of multiple families coming together around Yiddish language and culture.

I couldn’t possibly do justice to each of my subjects or share all the details that parents are eager to learn in the space of one article, which already far exceeded the target word count. So this page is an English-language supplement, consisting of some additional resources and links for parents and organizers, a more detailed description of the Stockholm Yiddish Club, and a full email interview with its co-organizer Sarah Sore Schulman (director of Dos Nisele).

UPDATE, 20 December — As I expected (and even hoped), the publication of the article has already sparked some dialogue on social media and exposed some of the holes in my reporting. I will continually update the “resources and links” section below, as I learn more information, so this is not a static page. In particular, I would like to mention the Kinderwelt club for parents and children at Warsaw’s Center for Yiddish Culture, and the Kindershul at the Paris Yiddish Center (which seems to be on pause from their website, but no doubt has useful resources). I’ll admit I wasn’t aware of either of them.

Resources and links for parents and organizers

This is a continuously updated list. If you have more useful tips that belongs here, please let me know! I’m trying to keep it concise.

If you have children age 5 or under with whom you speak Yiddish, reach out to Blima Jaclyn Granick for information on how to be added to the Whatsapp group for parents of Yiddish-speaking children. The Whatsapp group can also connect you with crowdsourced translations of English children’s books, which you can paste into the original books and read to your children.

You can order new Yiddish and bilingual children’s books from Kinder-Loshn Publications, Olniansky Tekst, Five Leaves, and Dos Nisele.

Some recent albums of songs for children are available via streaming and CD from Dos Nisele (featuring Sofia Berg-Böhm) and Borscht Beat (featuring Jordan Wax), and Botwinick Music (featuring David Botwinick, lyrics and translations available on the website).

Yiddish Pop is a free, child-friendly online Yiddish learning platform using animated videos.

Arun Viswanath compiled an invaluable compendium of traditional Yiddish children’s rhymes, games, and folklore, in this Google Doc. Another compendium he made specifically for Purim is available here.

Tomas Woodski compiled some games and vocabulary lists for children here on Isof’s website. The surrounding text is in Swedish, but the games themselves are in Yiddish.

The Swedish public broadcaster UR produces TV shows and videos suitable for children in Yiddish, some original and others adapted or translated from Swedish. You can browse and stream these here. Adult-oriented shows (which are still child-friendly but maybe less interesting to kids) are available here from SVT.

Katka Mazurczak (@katkeniu on Instagram) would be happy to share some of the many resources and materials she’s gathered as a Yiddish teacher at Stockholm’s weekly Yiddish Club and in Swedish schools, as well as a former employee of Isof, one of Sweden’s official institutions supporting minority languages in the country.

Funding for projects in Yiddish for children and youth is available from the Aaron and Sonia Fishman Foundation for Yiddish Culture. The applicant needs to be a US-registered nonprofit, but it might be possible to go through another organization. (If your country recognizes Yiddish as a minority language, exercise your rights and apply for funding!)

The organization Yugntruf has the mission of encouraging the active use of Yiddish among children and youth. Notably, they organize the annual Yiddish Vokh in Upstate New York, which is the biggest gathering of non-Hassidic Yiddish speakers (including families with children) every year.

The Wexler Oral History Project includes many interviews with people who organized or grew up in postwar Yiddish “shtetelekh” (small groups of Yiddish-speaking families). If you’re interested in this concept, I recommend watching the video interviews with Frederick Schwartzman, Rukhl Schaechter, and Anne Khane Eakin Moss.

More information about Yiddish as a recognized minority language in Sweden (and other useful resources) on the Yiddish website of Isof. Some other European countries, notably Poland, also recognize Yiddish as an official minority language under the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages. (Germany, where I live and where Yiddish probably first emerged, notably does not.) The types and amounts of support under the Charter vary by country, and the resulting projects are often useful to parents and language activists elsewhere.

Stockholm’s Yiddish Club (Jiddischklubben)

My article touched on Stockholm’s Yiddish Club (@Jiddischklubben), founded in September 2025 as a partnership between Dos Nisele (website in Swedish) and Sweden’s Yiddish Society (website in Yiddish and Swedish, Instagram: @jiddisch.se), but did not have space to go into much detail.

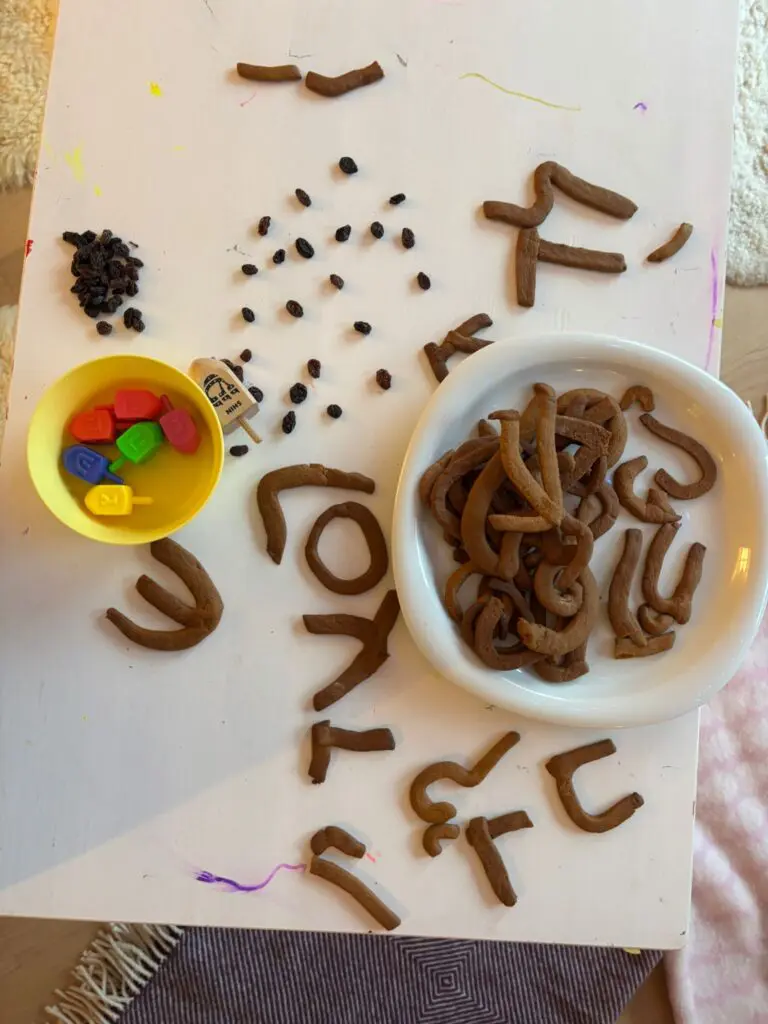

The group meets every Sunday for an hour, currently at a Jewish school, and welcomes all families with a connection to and/or interest in Yiddish to attend, whether or not you or your children have previous knowledge of the language. The classes are taught entirely in Yiddish, with a different theme every week, and include exercises and dances, singing, arts and crafts, stories, and more. The teacher, Katka Mazurczak, has a long history of involvement in many Yiddish projects starting with Yiddish radio in Poland.

Interview with Sarah Sore Schulman (Dos Nisele)

Berlin/Stockholm, 16 December 2025

While reporting for the article, I sent some interview questions to Sarah Sore Schulman, the founding director of “Dos Nisele” (Yiddish for “the Little Nut”), a publishing house and cultural organization based in Sweden. (Their website is in Swedish.) Her written responses, which went far beyond the article’s scope, were so detailed and informative that I have decided to publish them separately here.

What inspired you to start Jiddischklubben, the weekly Yiddish club for families with children in Stockholm?

It was a dynamic process. I had been running Dos Nisele for a few years and had quite some success with the publishing house (which is now more like a cultural production house). It felt natural honestly, I wasn’t happy with the slowness of the Jewish schools and kindergartens in bringing in Yiddish on the curriculum and I had tried accelerating the process with the Jewish Sunday school, where my kids were attending, but it was too slow. I had previously produced a playbox, Bubale Box, intended to teach small kids to learn Yiddish through play but nobody was using it. My children needed a space where Yiddish was at the center, and where Jewish values were at the core.

But I was looking for the right teacher, and suddenly stars aligned and Katke came into our lives. I should also say that I have been on the board of the Yiddish Society in Stockholm for many years, my father is heading the organization, and early on we decided to prioritize children. This initiative was part of that pledge, we had earlier been part of an animation course in Yiddish for children at the Jewish school, and of course organized several concerts and theatre plays within the Georg Riedel Yiddishland project (seע below).

My kids are the right age for something like this – that’s why it happened now. It has honestly become my most cherished activity with my children, and I love having that space with them, we all speak bloyz [only] yiddish and we sing and dance together with our kids. It is truly creating a better world. We also have families who only speak Yiddish with their kids, zealots, as well as families who have little Yiddish in their lives but want to re-connect. It’s a creative, cultural and Jewish space with lots of Yiddishkeyt. Don’t know what I would do without it now.

What is the role of Yiddish in your own family?

I grew up in a rich and vivid Yiddish house in Stockholm. My grandparents spoke Yiddish, survivors from the Holocaust, and Yiddish was my father’s mameloshn as a child growing up in Malmö. It was culturally rich, my zayde taught me Yiddish songs, he was also a real storyteller, my tate read tons of Yiddish literature to me, often in translations, but the culture was so close to me (Singer, Manger, Sholem Aleichem). I went to Jewish school in Stockholm but often wondered why my Jewish/Yiddish culture wasn’t present, there was an occasional Yiddish song here and there, but not much else. My sister picked up Yiddish with an amazing Yiddishist Lennart Kerbel z”l when she was around 14, I think that got the whole family going, including my tate. When I was in high school, I decided to write my thesis on how Yiddish became a recognized Swedish minority.

I started interviewing Yiddishists in Sweden, and got to know Eva Mannelid z”l, the first female head of the Yiddish Society. She later sent me to YIVO and Columbia University for the intensive zumer school, and there I really connected deep with my Yiddish Jewish identity. I never looked back. Yiddish is my creative space, my Jewish identity and what gives me a sense of purpose.

How should I describe Dos Nisele to our readers? Could you say something about the books you’ve published and your plans for the future?

Do you have any advice for parents in other places who might want to organize Yiddish groups for their own kids?

Yes, reach out to us! We have tons of material, play tools, rhymes, songs, TV programs, radio programs and books produced in Sweden for the global Yiddish community. We would love to help support more mishpokhes around the globe! Maybe we can start a pen pal club in Yiddish for our Yiddish kids?

Anything else I should know about related to the topic of connections and activities between Yiddishist families with children?

Something interesting, in Sweden children can demand mother-tongue lessons in Yiddish even if their families don’t speak the language. That’s a privilege all national minority languages have. More and more families request Yiddish for their children, but we don’t have enough teachers. When thinking about stimulating the Yiddish world for families and children, we should think about the whole ecosystem: theatre, films, books, music, education, communities, teachers and Yiddish clubs.